“Adapt and don’t give up:” How This Toronto Teacher Persevered to Help Children in Lebanon

Written by Bayan Yammout, who is UNICEF Canada Ambassador and special education teacher in Toronto, Ontario.

My suitcases were packed.

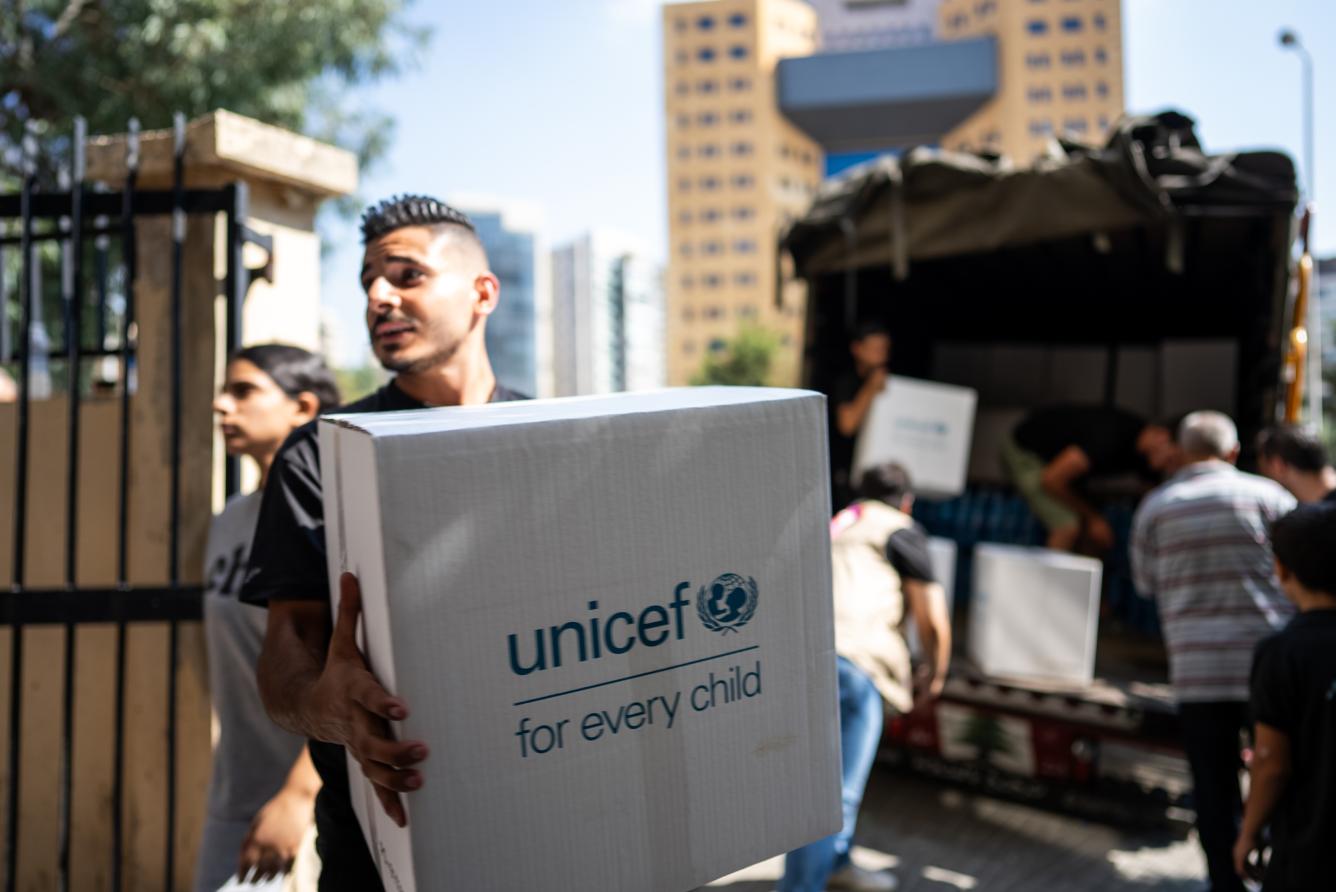

For weeks, I have been preparing to join the Equity & Inclusion team at UNICEF Lebanon and some of their specialized disability partner organizations. I was headed to the country’s north and then to the Bekaa region to support work on strengthening inclusive systems for children and youth with moderate to severe disabilities.

Together, we planned workshops for educators in Lebanon to share evidence-based, inclusive teaching practices and modelling sessions with the children inside the classrooms, including Makani Centres.

I was bringing along educational tools, materials, and picture books on topics like disability and inclusion. I was eager, excited, and nervous to be going back to help in my home country.

But on the morning of Sept 23rd, just four days before my scheduled flight to Beirut, I met with the team and decided to postpone my mission due to the escalating conflict.

A most difficult decision

In only a matter of days, heavy bombing had forcibly displaced 1.2 million people, including 400,000 children, and caused massive destruction and loss of life.

It should go without saying that this was not an easy decision for me. I felt guilty to accept the privilege of staying in a safe place while other humanitarians were risking their lives to help others.

But at that point, heavy bombardment had already reached many areas in Lebanon, including Beirut.

It simply wasn’t safe to go.

I wished I could do more for the families who must leave everything behind, unsure of when they might be back at their homes, and if it would still be standing. I thought of the conversations these parents must be trying to have with their frightened children. After all, how can you explain to a young child that staying home is no longer safe? How do you explain to a child that their home may be destroyed, or that all their precious treasures are gone?

I also thought of my parents. While they now live in Toronto, I had to remind myself of the fact that they know, first-hand, how it feels to always be on high alert; the stress and fear

they must have felt when my brother and I were walking home from school; and the pain they went through when losing family members, who where simply at the wrong place at the wrong time.

Even if I was willing to take the risk, I knew it wouldn’t be fair to have them experience those feelings again.

Same commitment, an innovative solution

Despite my disappointment, I remembered one of the many things I learned growing up during the civil war.

When a war stands between you and your plans, you focus on what you are still able to do. You take it day by day. You adapt and don’t give up. You focus on the present and plan for a peaceful tomorrow.

This is exactly what I did.

I kept in touch with UNICEF Lebanon, who were already prepared for the worse case scenario with a robust Response & Preparedness Plan to support Internally Displaced Persons. Part of this plan included “disability-inclusive programming targeting affected populations regardless of nationality” and “recreational activities to support children’s wellbeing and mental health, including for children with disabilities”—two things that immediately got my attention.

I knew that even if I couldn’t be physically on the ground running social-emotional activities, I could help create tools that educators and support staff in Lebanon would find useful.

I had to trust the war child in me and think back at what would have helped me when I lived through the war, then combine that with my knowledge as a Special Education Teacher. I had already worked with talented, multi-disciplinary teams to support children who have experienced trauma, serious illnesses, mental health challenges, as well as children who underwent recent amputations.

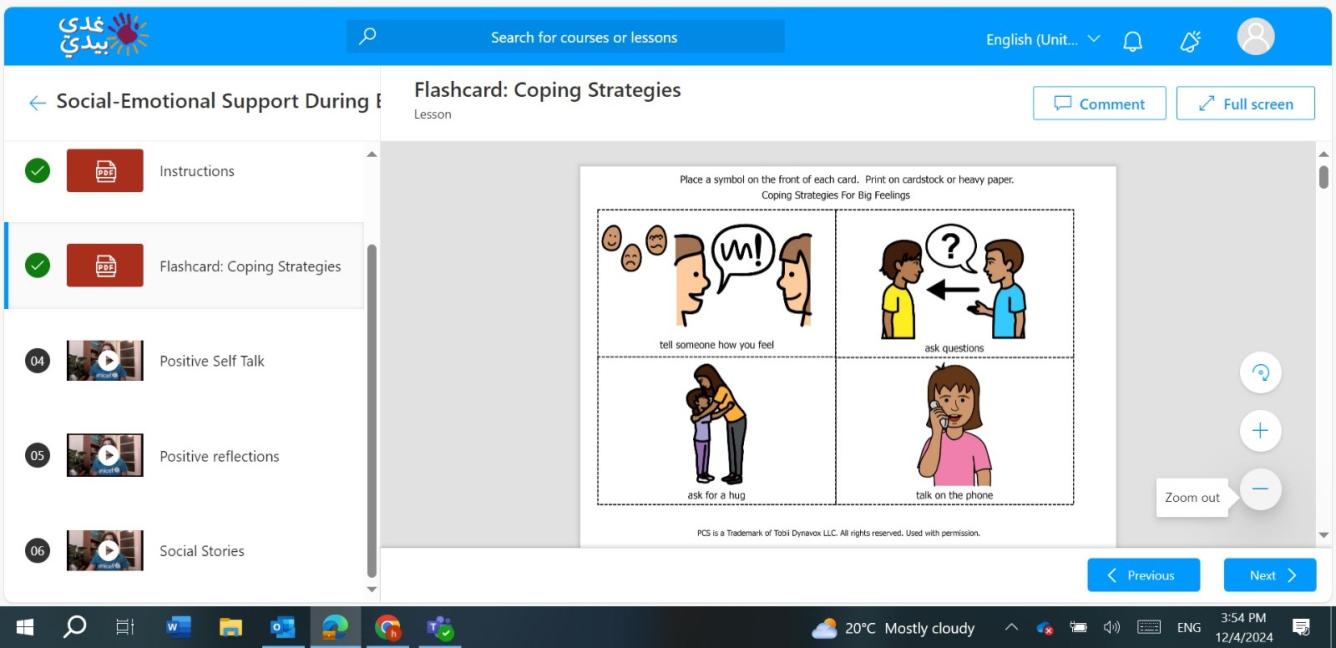

In consultation with the Equity & Inclusion Team at UNICEF Lebanon , and with the help of some of my former colleagues in the field, I developed visual tools to help young children, including children with disabilities, learn simple strategies to cope with strong emotions, such as fear, sadness, anxiety, and anger.

I also created a Social Story to help children process their emotions during the war. Originally developed by Carol Gray in 1990, Social Stories are short, illustrated stories that use simple and clear child-friendly language to explain a difficult situation and suggest ways to cope with ‘big feelings’ during unexpected distressing events. Social Stories are used mostly for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder but are beneficial for all young children. In addition, I put together tools to be used in “positive self-talk” and “positive reflection” recreational activities. Most of these tools are in Arabic and English.

On October 15th, I met online with 30 incredibly dedicated staff members and gave a presentation on Social-Emotional Support During Emergencies. I shared the tools and resources I created to support children and youth, with and without disabilities, during emergencies.

Those in attendance came from UNICEF Lebanon Save The Children, Humanity Inclusion, War Child, Al Hadi, CBRA, LOST, and FISTA, and they all demonstrated a strong commitment to supporting children in Lebanon. For instance, after a loud explosion was heard near one of the participants, they continued to stay connected after ensuring their safety.

What comes next…

In the next few weeks, the partners will implement those strategies as they see fit. They will also share them with caregivers and other educators through UNICEF’s online learning platform.

I continue to be available to support the teams during implementation and create more tools that could support the social and emotional wellbeing of children during emergencies. It may just be a little drop in the bucket, I believe that every drop counts.

Even though there is a ceasefire, children continue to experience high anxiety from the displacement, the scenes of destructions, and the lack of normalcy. Healing from this trauma will take a long time.

We know that all over the world, including here at home, children and youth with disabilities face physical, social, and attitudinal barriers. In countries affected by conflict, these children and their families face immense challenges and have a much higher mountain to climb, each day.

No child chooses to have a disability.

No child chooses to live in war.

As a global community, we must put every child first.

---

Bayan Yammout is a UNICEF Canada Ambassador and special education teacher in Toronto, Ont. Born in Beirut, Lebanon during the civil war, she spent 17 years living in a war zone. Today Bayan promotes UNICEF’s work in education and child protection during times of conflict. She was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee Medal in 2012 for her advocacy work with UNICEF Canada.